~While in Birmingham, Alabama last week, I visited Vulcan Park and Museum. It's on top of Red Mountain south of the city, which is riddled with old mine shafts from Birmingham's iron mining days. The park contains a museum and visitor's center, but the highlight is a huge statue of the Roman deity Vulcan, god of the Forge, on top of a brick tower:

^ A closer look at Vulcan. He's huge!

^ The statue was designed by Italian-born sculptor

Giuseppe Moretti, who created the hollow clay models for each piece of the statue in New Jersey. The clay casts were shipped by railroad to Birmingham, where workers from the Birmingham Steel and Iron Company worked feverishly to create the statue. They poured molten iron into each section of the hollow clay casts, allowed it to cool, and the cracked open the casts, revealing the completed cast-iron pieces. The pieces were assembled into the statue; all together, the combined body, forge, and spearpoint weigh 120,000 pounds.

^ Vulcan looking towards the moon

^ It's quite a climb to the top (I took the stairs -- all 119 of them -- instead of the elevator). The view of downtown Birmingham is worth it, though.

^ Taken from outside the visitor's center: the tower and the elevator frame a view of the moon.

^ The plaza outside of the visitor's center is a map of the area; the different colors indicate the geology of each area. See that skinny red line left of center? That's a vein of iron ore that runs through the area. It formed over 300 million years ago when iron-fixing bacteria congregated along a rock layer. In the present day, the reddish rocks are a common site on the appropriately-named Red Mountain and similar areas along the iron seam. The ore was mined, shipped into the city, and smelted to extract the iron from the ore.

^ Mining the iron ore was a tough business; the labor was intense and the rate of injuries and fatalities was high. But the booming industry attracted workers from all over the country. This display in the museum showed some of their stories. See the guy on the right? He was a convict, sentenced to hard labor in the iron mines as punishment for petty theft. His horrific death (tortured by overseers and thrown into boiling water) sparked national outrage to reform the convict-labor system that was widely in use at the turn of the century.

^ Different types of rock mined in the Birmingham area, and ingots of "pig iron" on the right. When ore is smelted to extract the iron, the resulting molten iron is channeled into a series of long containers to cool and harden. Because the containers resemble feeding troughs for pigs on a farm, it gave rise to the name pig iron. The pig iron provided a standardized shape that could be easily transported and melted down or worked later at another location.

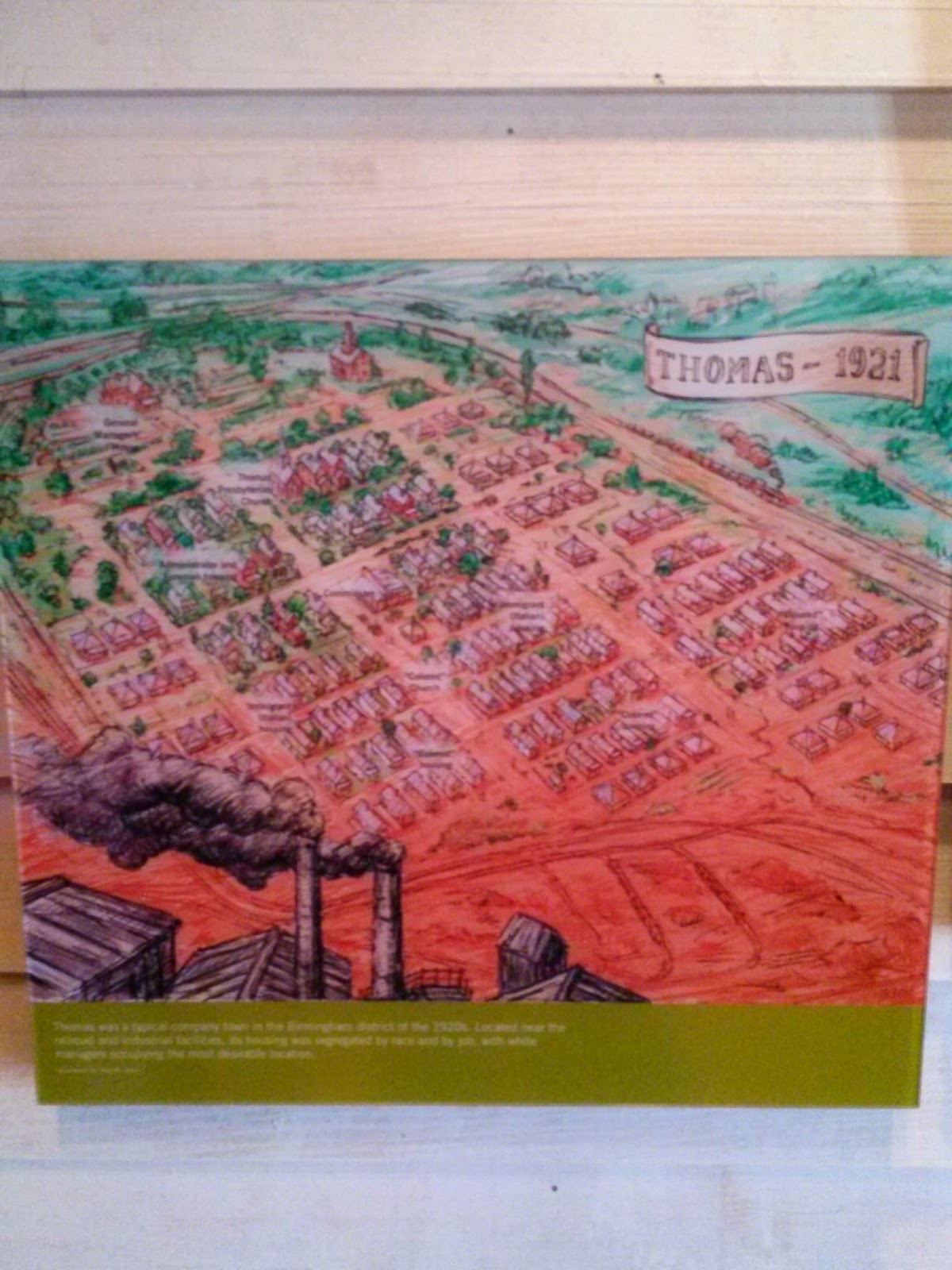

^ The industrial economy of Birmingham was dominated by a handful of large companies that controlled the entire iron process, from mining all the way to smelting, steelworking, and beyond. The labor force was often housed in company towns, where everything was owned by the company. Workers were provided housing and so forth, but this sometimes resulted in workers being trapped in the town, since they could owe more to the company stores than they earned. Above is a map of a company town in the Birmingham area from 1921.

^ Recreation of a company general store.

^ When Birmingham's iron mining economy began to take off in the late 1800s, the city government launched an ambitious plan for future expansion. Above is the grid plan they laid out and constructed, well before there was the population to accommodate such a large area. Their longsighted planning paid off: the booming economy attracted people in droves, and the grid provided an efficient layout for growth that still exists today. It uses a streets-and-avenues system that is immediately familiar to anyone who has spent time in Manhattan.

^ Map of the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis. During the Fair, the statue of Vulcan was housed in the Palace of Mines and Metallurgy (the rectangular building second from the left on the left edge of the map). The statue was a huge hit and won a Grand Prize. Several cities tendered offers to purchase the statue, but it was ultimately taken back to Birmingham.

^ After being shipped back to Birmingham, Vulcan spent the next three decades at the Alabama State Fairgrounds. He became a popular draw and advertising image, photographed or drawn holding ice cream, pickles, Coca-Cola, and other products. In the 1920s it was disassembled and repainted from the original gray to flesh tone. During a 1999 restoration, the statue was repainted gray and an internal metal skeleton was installed to support the formerly self-supporting statue, which had by that time begun to fall apart.

How fragile the works of man are! A metal statue, seemingly impervious to the elements, nearly laid low after less than a century of exposure to nature.

^ In the 1930s, a WPA project constructed Vulcan Park to house the statue at its present site atop Red Mountain, atop a 126-foot sandstone tower. In 1946, the chamber of commerce installed a neon light on the statue that would glow green, except during the 24 hours following any fatal traffic accident in the city, during which the light was changed to glow red.

^ During the 1904 World's Fair, souvenir statues of Vulcan sold like hot cakes. Today, they are prized collectibles. Here are some from the museum's collection.

^ Vulcan has inspired many pieces of artwork on display in the musueum. Remember, it's Vul-CAN, not Vul-CAN'T!

^ A futuristic Vulcan?

^ A more realistic depiction of Vulcan atop his tower.

^ Vulcan in stained glass.

^ Commemorative Vulcan plates.

^ Vulcan in LEGO: clearly the best piece of Vulcan art on display.

If you ever find yourself in Birmingham, Vulcan Park is well worth a visit. It's less than 15 minutes from downtown.